What is Brunello? It is pure Sangiovese from

Montalcino. It is aged for four years, with at least two of those in wooden barrels. It is the result of centuries of passion, experimentation, and success. It is a

Tuscan legend. It is all of this, but also much more. It is the living, vital expression of a community, a tradition, an identity. It is a chorus of hundreds of producers, with countless protagonists throughout the centuries. A thousand voices, but one extraordinary theme;

Brunello di Montalcino.

Siena, City State

The earliest mention of Brunello comes from this period. In his 16th-century Cronaca (Chronicles), Marcantonio Rigaccini writes, “Renai and Martoccia are the most famous vineyards of the era [and they produce] the best Brunello di Montalcino” (f. 22). In his 1551 Descrittione di tutta Italia (Description of Italy in its Entirety), historian Leandro Alberti writes that “as you then walk toward Siena, you discover Monte Alcino which lies on another mountain. It’s called ‘Mons Alcinoi by Volaterrano and it is renowned in the country for the good wines that come from its gentle hills.”

The Medici

During this period, “Montalcino [was] the only commune in the district where fine wine was produced for the market...” Even the royal court in England imported wines from Montalcino: Between 1688 and 1712 King William II served them at his table. There is evidence of this in the extensive correspondence between the English ambassador to Tuscany, Lord Evelyn, and the Court of St. James.

King Guglielmo III

King Guglielmo III

The renowned economist Federigo Melis, who studied Italian wine in the Middle Ages, wrote the following about Montalcinese viticulture: “Montalcino had already emerged” as a center for wine production “but the name Brunello doesn’t begin to appear until the late 16th century.”. From 1623 to 1644, the Montalcinese doctor Giulio Mancini served as archiater, chief physician to the Pope. He brought Pope Urban VIII a gift of wines from Montalcino, wines so renowned “for their vigor and for their flavor” that the Pope, a man of “greatly refined taste, often requested for himself and his court.”. According to a work published by Dante Vigiani in 1943, Montalcino wines were regularly exported to England by the second half of the 1600s.

The Lorraine Era

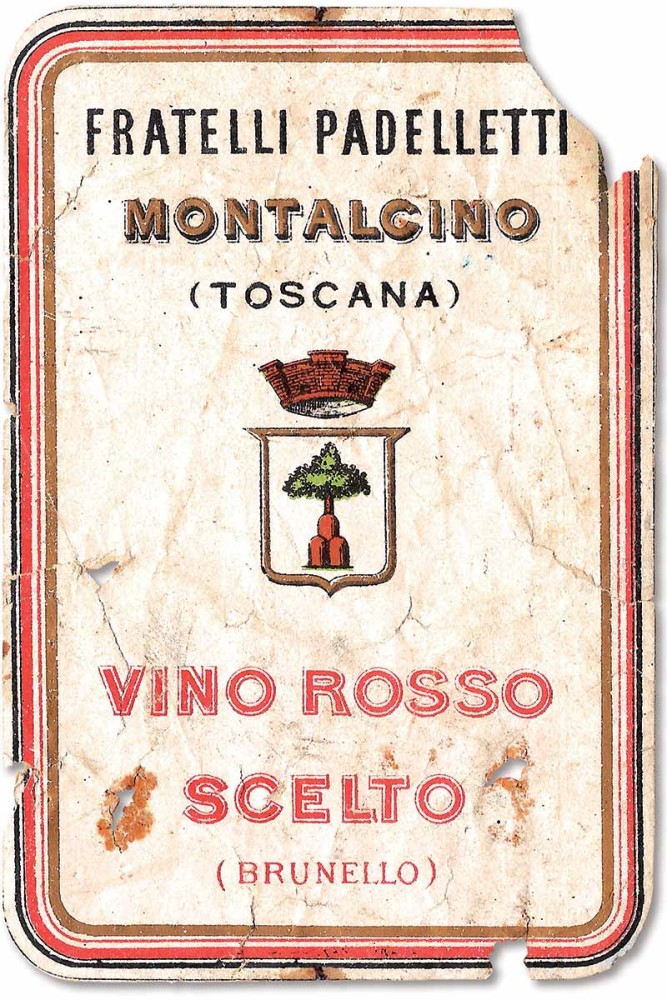

In this period the only industry that grew in Montalcino was wine. In 1676, 5,750 some or sums of wine had been produced (the equivalent of 700,000 bottles). By the early 1800s, 5,000 hectares were planted to vine. Today, there are 3,480 hectares planted to vine. Around 1750, Giovanni Antonio Pecci wrote that “Montalcino sits atop a steep hilltop. If the work and production of the country people wasn’t concentrated in farming, it certainly would be considered but a barren and inhabitable place. But the dense vineyards and other domestic trees makes it easy.” In 1770, the noted naturalist Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti wrote in “Riflessioni sopra la poca durata dei vini Toscani” (“Reflections on the Short Life of Tuscan Wine”) that the wines of Montalcino were superb in quality. They were among the few Tuscan wines, he wrote, that had excellent aging potential. Starting in 1820, the Padelletti brothers began selling bottles of Brunello with printed labels, an early and modest glimpse of the future to come.

From 1820, the Padelletti brothers begin selling Brunello bottles with labels printed in a typographic press, a signal of a different future.

From 1820, the Padelletti brothers begin selling Brunello bottles with labels printed in a typographic press, a signal of a different future.

In 1834, the illustrious agronomist Cosimo Ridolfi, who would become the president of the Tuscan Council in 1848, believed (as reported by Paolo Bellucci in I Lorena in Toscana [The Lorraine Dynasty in Tuscany]) that the wines of the time were mediocre and unsuitable for exportation. He held that they needed to improve to the point that “in Tuscany, everything would have to become ‘Chianti,’ ‘Pomino,’ ‘Carmignano,’ [or] ‘Montalcino,’ with established character in [the wines’] color, aroma, and flavor, in order to have fixed and general credit.” In other words, Brunello was one of the four best wines in Tuscany in the mind of the most famous agronomist in Tuscany at the time. And Brunello, as he wrote, was to be considered a model for all. In 1856, Clemente Santi presented his wines at exhibitions in London and Paris. And they were included in the “Catalog of reproductive animals, machines, tools, and agricultural products presented at the exhibition held from June 1-7, 1857” with “aged sparkling Vin Santo from Montalcino soils, aged Vin Santo, as above, [and] common Red Wine, as above.

1860 – 1918 Kingdom of Italy

In 1864, Dr. Clemente Santi presented four vintages of red wines to Farming Committee of Siena: 1860, 1861, 1862, and 1863. And Giuseppe Anghirelli presented a Vino Nero (“black” or red wine) and a Vino Rosso (red wine). According to the analyses of these wines, the description of the grapes and the vinification method, they were all Brunellos except for the Vino Nero. In 1869, Clemente, the son of Luigi Santi, was awarded the silver prize for an 1865 Brunello by the Montepulciano District Farming Committee. In 1970, Tito Costanti, the mayor of Montalcino, took part in the Siena Province Exhibition with an 1865 Brunello. In 1873, Gabriel Rosa, a noted patriot and intellectual from Bergamo who had made his name during the unification of Italy, wrote that “wine was the greatest and singular source of pride of the Siena territory. The wines of Brolio, Montepulciano, Montalcino, and Sinalunga are undoubtedly the best in Italy.” In 1874, Fattoria dei Barbi was awarded a silver medal by Italy’s Agriculture Ministry, the first national prize for a wine from Montalcino. Between 1875 and 1876, the Siena Province Ampelographic Commission published what is now the oldest extant analysis of a Brunello, including a chemical analysis and a tasting note. The wine in question was a Castelgiocondo produced by the Angelini family in 1843. At 32 years old, it was a wine that was still ruby red in color, with 14.2 percent alcohol, 5.1 total acidity, and 23.8 dry extract. These data align with the best Brunello (with similar age) today. The commission wrote that Brunello, Moscadello, and Procanico were the most widely planted grape varieties in Montalcino since ancient times. In 1885, Professor Sirio Martini, viticulture instructor at the Istituto Tecnico Vinicolo G.B. Cerletti (G.B. Cerletti Institute of Winemaking Technology) in Conegliano Veneto, held a conference in Siena on “the future riches of Siena Province.” He claimed that Chianti, Montepulciano, and Brunello di Montalcino were already well known and sold in all wine markets in Italy and abroad. Brunello in particular, thanks to the legendary harvests of 1888 and 1981. More than 100 prizes were won by Brunellos throughout Europe between 1860 and the First World War. They are evidence of the quality and vitality of viticulture in Montalcino toward the end of the 1800s. They are also a reflection of the community’s widespread passion for developing these wines. Brunello was well known among consumers but still hard to obtain. And it only represented a fraction of the wines produced in Montalcino. But it won awards in every European competition where it was presented. And many different producers brought home prizes. But early successes were threatened by the arrival of phylloxera, which first appeared in northern Tuscany in 1888. By 1903, it had arrived in Castelnuovo dell’Abate, a hamlet in Montalcino township. During that period, there were 3,800 hectares either planted solely to vine or planted to vine and other crops (today, there are 4,600 hectares). They all needed to be replanted because they all needed to be grafted to resistant American rootstock in order to eliminate the parasite. As a result, Montalcino’s thriving viticulture was put on hold for years.

In the 1870, Tito Costanti took part of the Siena provincial exhibition with a wine named Brunello.

In the 1870, Tito Costanti took part of the Siena provincial exhibition with a wine named Brunello.

1919 – 1945 between the World Wars

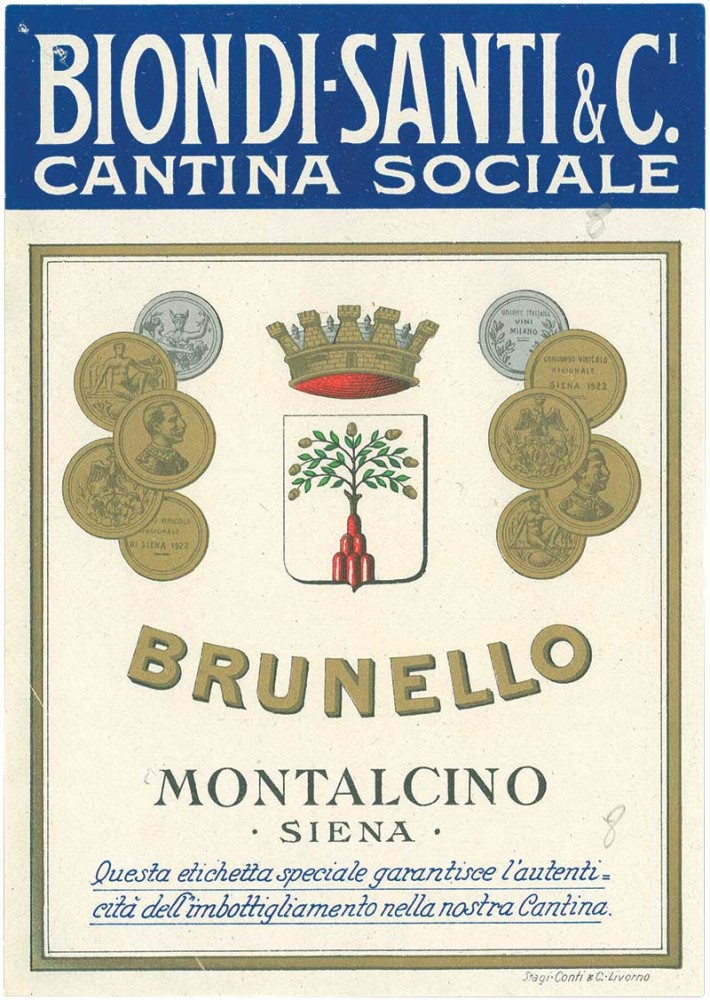

The city of Montalcino seemed in decline. Only Brunello continued to grow, however slowly. The quantity of bottles sold was still modest. But it was during this period that many in Montalcino began to adopt the practices that would become the basis for Brunello’s success as a quality wine. In 1926, Tancredi Biondi Santi founded the cooperative “Cantina Sociale Biondi Santi & C.” underneath the ancient Spedale di Santa Maria della Croce (today’s city hall). He was joined by eight top producers that decided to vinify and package their wines together. But all of them could sell their wines with their own labels. And they could also compete separately for prizes. It was an idea as novel at the time as it is futuristic today. In 1931, Fattoria dei Barbi sold Brunello “by correspondence” (the internet of the era) with a mailing to every lawyer and doctor in Italy. Together, they bought more than 10,000 bottles each year. And not long after, the Biondi Santi cooperative shipped bottles of Brunello to the U.S. They were the first high-priced Italian wines sold in what would become the principal markets of the future. In 1933, 10 wineries from Montalcino took part in the first “Market Exhibition of Representative Italian Wines” in Siena. Their collective output, they reported, was 4,850 hectoliters, the equivalent of 650,000 bottles — an enormous quality for the era. Not only did Brunello producers attend wine fairs in the 1930s, the did so together. And they formed one of the largest groups of exhibitors at the time. Montalcino even had a motto for the event, written by poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti: “Brunello is gasoline,” in other words, it fueled the motors of the world. Nearly all of them returned for the second gathering in 1935. In the catalog for that year’s fair, A. Musiani wrote: “.. It’s obtained by vinifying Brunello on its own... [The grape variety] has been universally recognized as a sub-variety of Sangioveto Grosso... But Brunello obtains its greatest value in its fourth or fifth year”. In 1941, Podestà Giovanni Colombini opened Italy’s first public wine shop in Montalcino’s ancient fortress. By law, the store could only sell locally packaged agricultural products. Authenticity, localized production, and the use of local culture and landmarks to promote local products — all concepts entirely in vogue today.

In the 1926, Tancredi Biondi Santi creates Biodni Santis & C. social cellar

In the 1926, Tancredi Biondi Santi creates Biodni Santis & C. social cellar

1946 – 1969 the Crisis

Every part of the Montalcino economy was impacted. And decline in each sector affected the others. As a result, the once prosperous city became one of the poorest in Tuscany. In just a few short years, it lost 70 percent of its population. Only a handful of the great estates that had made Brunello what it was survived. Some new, small, privately owned estates had appeared. But they were limited to cereal farming and ranching and didn’t produce wine. But it was thanks to these small farms that Montalcino now had the basis for renewal. In 1949, Fattoria dei Barbi opened the first Tuscan winery that was consistently open to the public. It offered tastings, sales, food, and guided visits. In 1955, Giovanni Colombini asked Sienese designer Vittorio Zani (1892-1972) to create a new label for his wines. And in 1957, Tancredi Biondi Santi did the same. Fattoria dei Barbi’s was blue. And the label designed for Biondi Santi’s Greppo estate was black and gold. Both would become legendary. And it didn’t happen by chance. Both estates engaged in focused marketing of their products just as modern sales channels were taking shape in Italy and abroad. An uncanny knack for marketing would help Greppo to sell 10,000 bottles in the 1970s while Fattoria dei Barbi would reach 100,000 and then 200,000 bottles sold. At the time, these were extraordinary figures for fine wine sales, the highest in Italy. In 1961, Luigi Veronelli published I Vini d’Italia (The Wines of Italy) and Brunello is noted as one of the best wines in Italy to pair with red meat. In 1963, the DOC system was established, the Denominazione di Origine Controllata (Designation of Controlled Origin), with legislation passed on July 12 of that year. In 1966 Brunello was the first red wine to be made a DOC and 14 years later, it would become the first DOCG or Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (Designation of Controlled and Guaranteed Origin), the highest official designation that the Italian government can confer. In 1967, 18 Montalcino producers formed the Consorzio del Vino Brunello (Consortium of Brunello Wine). Brunello had been officially recognized by the Italian government. The quantity of bottles sold and the wine’s notoriety had speed things up markedly. But the crisis still loomed. By this point, the number of grape growers had been reduced to 37, with 105 hectares authorized for the production of Brunello, including parcels planted solely to vine or planted to vine and other crops. Of the many pre-war era producers, only three still sold Brunello in bottle. In 1968, Giachetti and Milone’s Vini e Vigne d’Italia (Wines and Vines of Italy) mentions that Brunello is a wine with great aging potential. In 1969, Veronelli published his first Catalogo dei Vini Rossi d’Italia — Gotha dei Vini (Catalog of Red Wines of Italy — Wine Almanac). It included a Brunello by Biondi Santi with three stars, Fattoria dei Barbi with two stars, and Il Poggione with one star. It would only take a few years for the number of authorized hectares to increase to 470, with more than 100 producers. By 1980, the number of authorized hectares had grown to 693. Early on, there was a fragmentation between medium-sized, small, and very small grape growers. It would become one of the defining characteristics of the Montalcino wine industry. Despite the fact that Brunello began to show signs of growth, the 1960s were marked by an economy that remained depressed. In 1970, the Cencioni family’s Capanna estate became the first independent grower to bottle Brunello under its own label. The factors that would empower renewal were already in the works but the results weren’t yet visible.

Giovanni Colombini, owner of Fattoria dei Barbi

Giovanni Colombini, owner of Fattoria dei Barbi

1970 - 1989 Brunello delivers montalcino from its economic woes

In 1972, the second edition of Luigi Veronelli’s Catalogo dei Vini Rossi d’Italia — Gotha dei Vini (Catalog of Red Wines of Italy — Wine Almanac) listed three Brunellos, in the third “catalog,” published in 1974, the number of wineries included grew to five, in the fourth “catalog,” released in 1976, there are six. In those years, there were few Italian fine wine producers who exported their labels — less than 100. But ten of them were in Montalcino. In 1978, Monte dei Paschi di Siena published an “analysis of certain aspects of the Sienese economy.” According to the findings, Montalcino had the highest average income per capita in Siena province. At the time, there were 93 grape growers in Montalcino with 693 hectares planted to Brunello. The appellation produced 4,034,320 bottles that year, nearly all of them by local grape growers. That same year, Burton Anderson, arguably the most well-known wine writer of the era, he describes Brunello as Italy’s best wine. And he notes that pricing for certain wines has surpassed that of grand cru wines from France. On the heels of the appellation’s success in the first half of the decade, Wine Spectator included two Brunello producers among the top 100 wineries in the world presented at the first-ever New York Wine Experience tasting in 1985. By this point, Brunello was Italy’s most lucrative high-end wine. And the appellation’s spot at the top would remain unchanged for the next four decades. Italian and foreign entrepreneurs had taken note of Brunello’s impressive growth, high prices, branding successes, and the fact that it could be found in every market in the world. And they decided to invest in Montalcino. The first 10 or so “non-local” grape growers arrived at the end of the 1970s. Over the course of the next two decades, their number would grow to represent roughly a third of Montalcino’s output and a third of the wineries as a whole. In 1984, Brunello became the first Italian wine to become a DOCG appellation. At the same time, Rosso di Montalcino became a DOC — the first “second tier” wine in the country. It was a significant innovation that had been studied and implemented by the commune and by the president of the Brunello Consortium, Enzo Tiezzi. In 1988, the Montalcino township and the Brunello Consortium organized a celebration of Brunello’s first 100 years. An idea conceived by Franco Biondi Santi, it included four bottles of Biondi Santi’s 1888 Brunello Il Greppo as its centerpiece. It was the Italian wine industry’s first large media event and a consecration of Brunello on an international level. Montalcino became a small but rich capital of the Italian wine world. It was still provincial but dynamic and globalized, with myriad businesses of every size that continued to evolve and compete. The city’s development came with extremely high rates of growth. But it was solidly grafted on to ancient roots full of life.

In the 1984, the Brunello is the first wine in italy to obtain the DOCG mark

In the 1984, the Brunello is the first wine in italy to obtain the DOCG mark

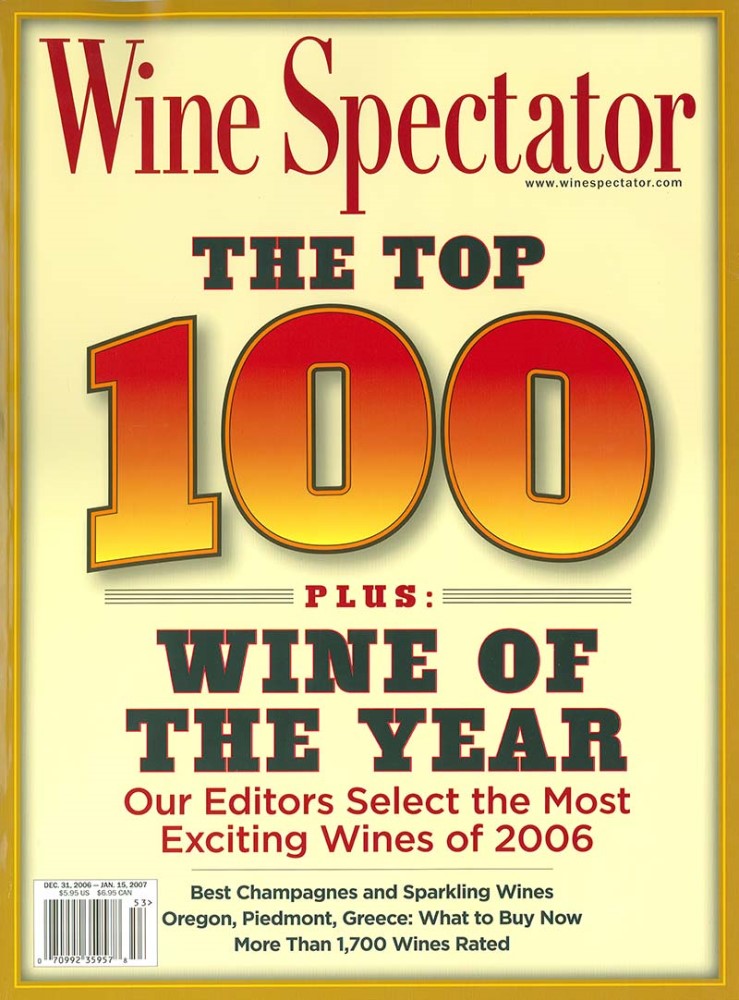

1990 - 2008 Brunellos first Golden Age

he 1990 harvest was the first great vintage of Brunello’s “golden age.” Of the 2,536,274 bottles that were released, many of them had doubled in price with respect to the 1989 vintage. In 1993, the president of the Brunello Consortium, Sante Turone from the Caparzo winery, created Benvenuto Brunello. It was a tasting of the DOCG and DOC wines from nearly all the wineries in Montalcino. And it was held at Banfi’s cinematic castle, the Castello di Poggio alle Mura. The event marked the birth of the “preview” tastings, a marketing model that became enormously successful and was soon imitated across Italy. At the 1993 gathering, 200 journalists from the world’s most important mastheads were in attendance. Thousands of articles were published following the tasting. In just a few short years, the number of hectares planted to Brunello in Montalcino rose from 1,260 to 2,100. And the number of hectares planted to Rosso di Montalcino went from a handful to 550. In 2000, sales of Brunello climbed to 4,608,562, nearly double the number of bottles sold ten years prior. In 2002, the legendary 1997 vintage of Brunello was released. Once again, Brunello was a huge hit among consumers and critics alike. The market was so taken with the “vintage of the century” that it tolerated unbelievable price increases. In 2005, Censis (Centro Studi Investimenti Sociali or Center for the Study of Social Investment) reported that more than 2 million tourists were visiting Montalcino each year. That’s 384 visitors per resident, the highest ratio between visitors and inhabitants in all of Italy. In 2006, Wine Spectator named Casanova di Neri’s Brunello the best wine in the world. But that was just one of the myriad awards received by more than 100 Montalcino wineries. By this point, there were more than 240 bottlers of Brunello, with 6,854,234 bottles sold. From 1990 until 2008, quantities of Brunello sold increased by nearly six percent each year. And prices increased at a similar rate as well. The Brunello brand had grown markedly, and some wineries were now famous throughout the world. During this period, many wineries vied for the top ratings and classifications in wine guides and magazines. Soldera-Case Basse was one of the first to stand out, later followed by Poggio Antico, and in subsequent years by Cerbaiona and Casanova di Neri. It was probably during this period that the Brunello brand became more important than the winery brands. Today, it remains, arguably, the most recognizable Italian wine brand in the world.

In the 2006, the Brunello of Casanova di Neri is the best wine in the world by the words of “Wine Spectator”

In the 2006, the Brunello of Casanova di Neri is the best wine in the world by the words of “Wine Spectator”

2009 - 2018 fall and rise

On September 11, 2008 the banking services firm Lehman Brothers in New York went bankrupt. It was the beginning of a financial crisis that would span the world. Montalcino was affected by a series of negative events simultaneously. The decision to increase Brunello production in 1997 caused supply to rise by 50 percent just as demand was collapsing. At the same time, Italian authorities were conducting an investigation of certain wineries suspected of having added unauthorized grapes to their Brunello. The so-called “Brunello scandal” had terrible consequences in the media, with thousands of articles in nearly every newspaper across the world calling into question the practices of Montalcino grape growers. It was a true annus horribilis. The price of bulk wine dropped from €900 per hectoliter to €300. And bottle sales also dropped. In 2009, Montalcino wineries had 47,216.400 bottles of Brunello in their cellars, 9,241,067 more than they had in 2005. In just a short time, they had accumulated a surplus equivalent to a year and a half of sales. Many wineries’ sales dropped considerably but by 2012, they began to pick up again. In just six years, Montalcino was able to overcome an extremely challenging situation. Even though no wineries closed or were sold off, it radically reshaped the appellation. The frequent and often severe monitoring in the wake of the scandal had an unexpected result: It caused quality and consumer confidence to rise. As a result, Brunello sales rose from roughly 6 million bottles at the beginning of the century to nearly 10 million. And the prices were higher than ever before. The 2009-2015 crisis inspired nearly every winery to make production more efficient. And many updated their winemaking technology. The vineyards were monitored by officials as well. As a result, farming practices became more environmentally friendly and there were many cases where estates adopted organic or biodynamic practices. It’s rare that grasses aren’t allowed to grow between the rows in Montalcino’s vineyards these days. The olive groves are maintained immaculately. And you never see an abandoned field or farm here. Nearly every business in Montalcino felt compelled to improve its marketing and public relations. This resulted in better positioning for Brunello and a number of Montalcino estates. In 2018, Casanova di Neri’s Brunello was awarded the fourth highest score in the world by Wine Spectator and Altesino’s was awarded the eleventh highest score. The editors of Wine Advocate gave Le Chiuse’s Brunello their second highest score while Ciacci Piccolomini’s received their thirteenth highest score. As Friedrich Nietzsche once wrote, what does not kill me makes me stronger. Montalcino had created the most lucrative agriculture in Italy.

From 2019…. – Montalcino’s future?

This work would be incomplete without some mention of today's

Montalcino. On January 1, 2017,

Montalcino merged with San Giovanni d’Asso. The population rose to 6,043 inhabitants and the area to 31,013 hectares. Agriculture employs two thousand people, reaching 2,600 during peak periods. The vineyard covers 3,480 hectares, of which 2,100 are registered as

Brunello di Montalcino DOCG, 510 as

Rosso di Montalcino DOC, 38 as

Chianti DOCG, and 832 as

Sant’Antimo DOC or

IGT Toscana. The Sangiovese grape covers 2,750 hectares, accounting for 80% of the total. However, if we exclude the three companies with the highest percentage of different grapes, we obtain a remarkable result: the remaining 300 companies have 2,480 hectares of Sangiovese out of 2,560, or 97%. From 2011 to 2019, many wineries have been renewed, and high-quality tourist facilities have been established, but the most important aspect is that 887 hectares of vineyards have been planted. We have reached 4,315, a +24% increase in eight years. Success has not concentrated production in the hands of a few. The 10 largest companies produce one-third of

Brunello, another third comes from 40 medium-sized wineries, while the rest is produced by smaller ones. The people of Montalcino own two-thirds of the vineyards, which explains the strong link between the wines and the territory. Today, capital is seeking investments in unique assets like Brunello, resulting in approximately 5% of

Montalcino's vineyards changing ownership, including the historic brand

Biondi Santi, along with the well-known brands Cerbaiona and Poggio Antico, plus several smaller ones. Will success continue? It is likely, as it is tied to stable factors: the strength of the Brunello brand, low competition on price, the impossibility of increasing production, and a growing global market for prestige products. Here, it is more advantageous to compete on quality and image rather than price, creating a virtuous cycle: product improvement is appreciated by customers and the media, enhancing the

Brunello brand and increasing bottle prices. This generates more resources for further enhancing quality and image, sustaining the cycle. In 2020, we sold Brunello 2015, the record-breaking vintage; in the history of wine, never before had so many wineries of a single Denomination received so many top scores (100/100, 20/20, and similar). Then came COVID-19. In 2021? James Suckling and then all the major wine journals worldwide crowned Brunello 2016. In the world's most important wine ranking, the "Top 100" of "Wine Spectator," two Brunellos appeared in the top twenty, which, as often happens here, were not the usual suspects: third place went to San Filippo, and sixteenth to Caprili. In 2022, Brunello reaffirmed its value with another great achievement:

Fattoria dei Barbi secured second place in Wine Spectator's ranking, further strengthening the denomination's international reputation. In 2023, something extraordinary and unprecedented in wine history happened: Wine Spectator awarded

Argiano as the best wine in the world, and Wine Enthusiast did the same with

Poggio di Sotto. This marks the first and only time that the two most important wine magazines have, in the same year, chosen a wine from the same Denomination as the best.

Montalcino seems to be emerging from this crisis, reaffirming itself as something unique and different from all others: a play with the same actors, but who continuously switch roles in a highly adaptable and dynamic scene.